- Home

- Oscar Wilde

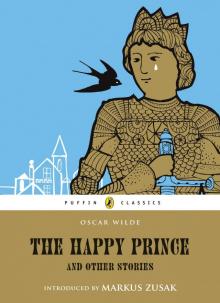

The Happy Prince & Other Stories (Puffin Classics Relaunch) Page 3

The Happy Prince & Other Stories (Puffin Classics Relaunch) Read online

Page 3

‘“Real friends should have everything in common,” the Miller used to say, and little Hans nodded and smiled, and felt very proud of having a friend with such noble ideas.

‘Sometimes, indeed, the neighbours thought it strange that the rich Miller never gave little Hans anything in return, though he had a hundred sacks of flour stored away in his mill, and six milch cows, and a large flock of woolly sheep; but Hans never troubled his head about these things, and nothing gave him greater pleasure than to listen to all the wonderful things the Miller used to say about the unselfishness of true friendship.

‘So little Hans worked away in his garden. During the spring, the summer, and the autumn he was very happy, but when the winter came, and he had no fruit or flowers to bring to the market, he suffered a good deal from cold and hunger, and often had to go to bed without any supper but a few dried pears or some hard nuts. In the winter, also, he was extremely lonely, as the Miller never came to see him then.

‘“There is no good in my going to see little Hans as long as the snow lasts,” the Miller used to say to his wife, “for when people are in trouble they should be left alone and not be bothered by visitors. That at least is my idea about friendship, and I am sure I am right. So I shall wait till the spring comes, and then I shall pay him a visit, and he will be able to give me a large basket of primroses, and that will make him so happy.”

‘“You are certainly very thoughtful about others,” answered the Wife, as she sat in her comfortable armchair by the big pinewood fire; “very thoughtful indeed. It is quite a treat to hear you talk about friendship. I am sure the clergyman himself could not say such beautiful things as you do, though he does live in a three-storied house, and wear a gold ring on his little finger.”

‘“But could we not ask little Hans up here?” said the Miller’s youngest son. “If poor Hans is in trouble I will give him half my porridge, and show him my white rabbits.”

‘“What a silly boy you are!” cried the Miller; “I really don’t know what is the use of sending you to school. You seem not to learn anything. Why, if little Hans came up here, and saw our warm fire, and our good supper, and our great cask of red wine, he might get envious, and envy is a most terrible thing, and would spoil anybody’s nature. I certainly will not allow Hans’ nature to be spoiled. I am his best friend, and I will always watch over him, and see that he is not led into any temptations. Besides, if Hans came here, he might ask me to let him have some flour on credit, and that I could not do. Flour is one thing, and friendship is another, and they should not be confused. Why, the words are spelt differently, and mean quite different things. Everybody can see that.”

‘“How well you talk!” said the Miller’s Wife, pouring herself out a large glass of warm ale; “really I feel quite drowsy. It is just like being in church.”

‘“Lots of people act well,” answered the Miller; “but very few people talk well, which shows that talking is much the more difficult thing of the two, and much the finer thing also”; and he looked sternly across the table at his little son, who felt so ashamed of himself that he hung his head down, and grew quite scarlet and began to cry into his tea. However, he was so young that you must excuse him.’

‘Is that the end of the story?’ asked the Water-rat.

‘Certainly not,’ answered the Linnet, ‘that is the beginning.’

‘Then you are quite behind the age,’ said the Water-rat. ‘Every good storyteller nowadays starts with the end, and then goes on to the beginning, and concludes with the middle. That is the new method. I heard all about it the other day from a critic who was walking round the pond with a young man. He spoke of the matter at great length, and I am sure he must have been right, for he had blue spectacles and a bald head, and whenever the young man made any remark, he always answered “Pooh!” But pray go on with your story. I like the Miller immensely. I have all kinds of beautiful sentiments myself so there is a great sympathy between us.’

‘Well,’ said the Linnet, hopping now on one leg and now on the other, ‘as soon as the winter was over, and the primroses began to open their pale yellow stars, the Miller said to his wife that he would go down and see little Hans.

‘“Why, what a good heart you have!” cried his Wife; “you are always thinking of others. And mind you take the big basket with you for the flowers.”

‘So the Miller tied the sails of the windmill together with a strong iron chain, and went down the hill with the basket on his arm.

‘“Good morning, little Hans,” said the Miller.

‘“Good morning,” said Hans, leaning on his spade, and smiling from ear to ear.

‘“And how have you been all the winter?” said the Miller.

‘“Well, really,” cried Hans, “it is very good of you to ask, very good indeed. I am afraid I had rather a hard time of it, but now the spring has come, and I am quite happy, and all my flowers are doing well.”

‘“We often talked of you during the winter, Hans,” said the Miller, “and wondered how you were getting on.”

‘“That was kind of you,” said Hans; “I was half afraid you had forgotten me.”

‘“Hans, I am surprised at you,” said the Miller; “friendship never forgets. That is the wonderful thing about it, but I am afraid you won’t understand the poetry of life. How lovely your primroses are looking, by-the-bye!”

‘“They are certainly very lovely,” said Hans, “and it is a most lucky thing for me that I have so many. I am going to bring them into the market and sell them to the Burgomaster’s daughter, and buy back my wheelbarrow with the money.”

‘“Buy back your wheelbarrow? You don’t mean to say you have sold it? What a very stupid thing to do!”

‘“Well, the fact is,” said Hans, “that I was obliged to. You see the winter was a very bad time for me, and I really had no money at all to buy bread with. So I first sold the silver buttons off my Sunday coat, and then I sold my silver chain, and then I sold my big pipe, and at last I sold my wheelbarrow. But I am going to buy them all back again now.”

‘“Hans,” said the Miller, “I will give you my wheelbarrow. It is not in very good repair, indeed, one side is gone, and there is something wrong with the wheel spokes, but in spite of that I will give it to you. I know it is very generous of me, and a great many people would think me extremely foolish for parting with it, but I am not like the rest of the world. I think that generosity is the essence of friendship, and, besides, I have got a new wheelbarrow for myself. Yes, you may set your mind at ease, I will give you my wheelbarrow.”

‘“Well, really, that is generous of you,” said little Hans, and his funny round face glowed all over with pleasure. “I can easily put it in repair, as I have a plank of wood in the house.”

‘“A plank of wood!” said the Miller; “why, that is just what I want for the roof of my barn. There is a very large hole in it, and the corn will all get damp if I don’t stop it up. How lucky you mentioned it! It is quite remarkable how one good action always breeds another. I have given you my wheelbarrow, and now you are going to give me your plank. Of course, the wheelbarrow is worth far more than the plank, but true friendship never notices things like that. Pray get it at once, and I will set to work at my barn this very day.”

‘“Certainly,” cried little Hans, and he ran into the shed and dragged the plank out.

‘“It is not a very big plank,” said the Miller, looking at it, “and I am afraid that after I have mended my barn-roof there won’t be any left for you to mend the wheelbarrow with; but, of course, that is not my fault. And now, as I have given you my wheelbarrow, I am sure you would like to give me some flowers in return. Here is the basket, and mind you fill it quite full.”

‘“Quite full?” said little Hans, rather sorrowfully, for it was really a very big basket, and he knew that if he filled it he would have no flowers left for the market, and he was very anxious to get his silver buttons back.

‘“Well, really,” answered the Miller, “as I hav

e given you my wheelbarrow, I don’t think that it is much to ask you for a few flowers. I may be wrong, but I should have thought that friendship, true friendship, was quite free from selfishness of any kind.”

‘“My dear friend, my best friend,” cried little Hans, “you are welcome to all the flowers in my garden. I would much sooner have your good opinion than my silver buttons, any day”; and he ran and plucked all his pretty primroses, and filled the Miller’s basket.

‘“Good-bye, little Hans,” said the Miller, and he went up the hill with the plank on his shoulder, and the big basket in his hand.

‘“Good-bye,” said little Hans, and he began to dig away quite merrily, he was so pleased about the wheelbarrow.

‘The next day he was nailing up some honeysuckle against the porch, when he heard the Miller’s voice calling to him from the road. So he jumped off the ladder, and ran down the garden, and looked over the wall.

‘There was the Miller with a large sack of flour on his back.

‘“Dear little Hans,” said the Miller, “would you mind carrying this sack of flour for me to market?”

‘“Oh, I am so sorry,” said Hans, “but I am really very busy today. I have got all my creepers to nail up, and all my flowers to water, and all my grass to roll.”

‘“Well, really,” said the Miller, “I think, that considering that I am going to give you my wheelbarrow it is rather unfriendly of you to refuse.”

‘“Oh, don’t say that,” cried little Hans, “I wouldn’t be unfriendly for the whole world”; and he ran in for his cap, and trudged off with the big sack on his shoulders.

‘It was a very hot day, and the road was terribly dusty, and before Hans had reached the sixth milestone he was so tired that he had to sit down and rest. However, he went on bravely, and at last he reached the market. After he had waited there for some time, he sold the sack of flour for a very good price, and then he returned home at once, for he was afraid that if he stopped too late he might meet some robbers on the way.

‘“It has certainly been a hard day,” said little Hans to himself as he was going to bed, “but I am glad I did not refuse the Miller, for he is my best friend and, besides, he is going to give me his wheelbarrow.”

‘Early the next morning the Miller came down to get the money for his sack of flour, but little Hans was so tired that he was still in bed.

‘“Upon my word,” said the Miller, “you are very lazy. Really, considering that I am going to give you my wheelbarrow, I think you might work harder. Idleness is a great sin, and I certainly don’t like any of my friends to be idle or sluggish. You must not mind my speaking quite plainly to you. Of course I should not dream of doing so if I were not your friend. But what is the good of friendship if one cannot say exactly what one means? Anybody can say charming things and try to please and to flatter, but a true friend always says unpleasant things, and does not mind giving pain. Indeed, if he is a really true friend he prefers it, for he knows that then he is doing good.”

‘“I am very sorry,” said little Hans, rubbing his eyes and pulling off his nightcap, “but I was so tired that I thought I would lie in bed for a little time, and listen to the birds singing. Do you know that I always work better after hearing the birds sing?”

‘“Well, I am glad of that,” said the Miller, clapping little Hans on the back, “for I want you to come up to the mill as soon as you are dressed and mend my barn-roof for me.”

‘Poor little Hans was very anxious to go and work in his garden, for his flowers had not been watered for two days, but he did not like to refuse the Miller, as he was such a good friend to him.

‘“Do you think it would be unfriendly of me if I said I was busy?” he inquired in a shy and timid voice.

‘“Well, really,” answered the Miller, “I do not think it is much to ask of you, considering that I am going to give you my wheelbarrow; but, of course, if you refuse I will go and do it myself.”

‘“Oh! on no account,” cried little Hans and he jumped out of bed, and dressed himself and went up to the barn.

‘He worked there all day long, till sunset, and at sunset the Miller came to see how he was getting on.

‘“Have you mended the hole in the roof yet, little Hans?” cried the Miller in a cheery voice.

‘“It is quite mended,” answered little Hans, coming down the ladder.

‘“Ah!” said the Miller, “there is no work so delightful as the work one does for others.”

‘“It is certainly a great privilege to hear you talk,” answered little Hans, sitting down and wiping his forehead, “a very great privilege. But I am afraid I shall never have such beautiful ideas as you have.”

‘“Oh! they will come to you,” said the Miller, “but you must take more pains. At present you have only the practice of friendship; some day you will have the theory also.”

‘“Do you really think I shall?” asked little Hans.

‘“I have no doubt of it,” answered the Miller, “but now that you have mended the roof, you had better go home and rest, for I want you to drive my sheep to the mountain tomorrow.”

‘Poor little Hans was afraid to say anything to this, and early the next morning the Miller brought his sheep round to the cottage, and Hans started off with them to the mountain. It took him the whole day to get there and back; and when he returned he was so tired that he went off to sleep in his chair, and did not wake up till it was broad daylight.

‘“What a delightful time I shall have in my garden!” he said, and he went to work at once.

‘But somehow he was never able to look after his flowers at all, for his friend the Miller was always coming round and sending him off on long errands, or getting him to help at the mill. Little Hans was very much distressed at times, as he was afraid his flowers would think he had forgotten them, but he consoled himself by the reflection that the Miller was his best friend. “Besides,” he used to say, “he is going to give me his wheelbarrow, and that is an act of pure generosity.”

‘So little Hans worked away for the Miller, and the Miller said all kinds of beautiful things about friendship, which Hans took down in a notebook, and used to read over at night, for he was a very good scholar.

‘Now it happened that one evening little Hans was sitting by his fireside when a loud rap came at the door. It was a very wild night, and the wind was blowing and roaring round the house so terribly that at first he thought it was merely the storm. But a second rap came, and then a third, louder than any of the others.

‘“It is some poor traveller,” said little Hans to himself and he ran to the door.

‘There stood the Miller with a lantern in one hand and a big stick in the other.

‘“Dear little Hans,” cried the Miller, “I am in great trouble. My little boy has fallen off a ladder and hurt himself, and I am going for the Doctor. But he lives so far away, and it is such a bad night, that it has just occurred to me that it would be much better if you went instead of me. You know I am going to give you my wheelbarrow, and so it is only fair that you should do something for me in return.”

‘“Certainly,” cried little Hans, “I take it quite as a compliment your coming to me, and I will start off at once. But you must lend me your lantern, as the night is so dark that I am afraid I might fall into the ditch.”

‘“I am very sorry,” answered the Miller, “but it is my new lantern, and it would be a great loss to me if anything happened to it.”

‘“Well, never mind, I will do without it,” cried little Hans, and he took down his great fur coat, and his warm scarlet cap, and tied a muffler round his throat, and started off.

‘What a dreadful storm it was! The night was so black that little Hans could hardly see, and the wind was so strong that he could hardly stand. However, he was very courageous, and after he had been walking about three hours, he arrived at the Doctor’s house, and knocked at the door.

‘“Who is there?” cried the Doctor, putting his head out of

his bedroom window.

‘“Little Hans, Doctor.”

‘“What do you want, little Hans?”

‘“The Miller’s son has fallen from a ladder, and has hurt himself, and the Miller wants you to come at once.”

‘“All right!” said the Doctor; and he ordered his horse, and his big boots, and his lantern, and came downstairs, and rode off in the direction of the Miller’s house, little Hans trudging behind him.

‘But the storm grew worse and worse, and the rain fell in torrents, and little Hans could not see where he was going, or keep up with the horse. At last he lost his way, and wandered off on the moor, which was a very dangerous place, as it was full of deep holes, and there poor little Hans was drowned. His body was found the next day by some goatherds, floating in a great pool of water, and was brought back by them to the cottage.

‘Everybody went to little Hans’ funeral, as he was so popular; and the Miller was the chief mourner.

‘“As I was his best friend,” said the Miller, “it is only fair that I should have the best place”; so he walked at the head of the procession in a long black cloak, and every now and then he wiped his eyes with a big pocket-handkerchief.

‘“Little Hans is certainly a great loss to everyone,” said the Blacksmith, when the funeral was over, and they were all seated comfortably in the inn, drinking spiced wine and eating sweet cakes.

‘“A great loss to me at any rate,” answered the Miller; “why, I had as good as given him my wheelbarrow, and now I really don’t know what to do with it. It is very much in my way at home, and it is in such bad repair that I could not get anything for it if I sold it. I will certainly take care not to give away anything again. One certainly suffers for being generous.”’

‘Well?’ said the Water-rat, after a long pause.

‘Well, that is the end,’ said the Linnet.

‘But what became of the Miller?’ asked the Water-rat.

‘Oh! I really don’t know,’ replied the Linnet; ‘and I am sure that I don’t care.’

‘It is quite evident then that you have no sympathy in your nature,’ said the Water-rat.

The Picture of Dorian Gray

The Picture of Dorian Gray The Importance of Being Earnest

The Importance of Being Earnest An Ideal Husband

An Ideal Husband Miscellaneous Aphorisms; The Soul of Man

Miscellaneous Aphorisms; The Soul of Man The Happy Prince and Other Tales

The Happy Prince and Other Tales The Canterville Ghost: Annotated

The Canterville Ghost: Annotated The Wit and Wisdom of Oscar Wilde

The Wit and Wisdom of Oscar Wilde The Complete Plays

The Complete Plays The Short Stories of Oscar Wilde

The Short Stories of Oscar Wilde The Importance of Being Earnest: And Other Plays

The Importance of Being Earnest: And Other Plays The Happy Prince (Oscar Wilde Classics)

The Happy Prince (Oscar Wilde Classics) Shorter Prose Pieces

Shorter Prose Pieces Importance of Being Earnest

Importance of Being Earnest Selected Tales: Shorter Prose Pieces

Selected Tales: Shorter Prose Pieces The Penny Dreadfuls MEGAPACK™

The Penny Dreadfuls MEGAPACK™ The Complete Short Fiction

The Complete Short Fiction The Illustrated Salomé in English & French (with Active Table of Contents)

The Illustrated Salomé in English & French (with Active Table of Contents) The Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray

The Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray Oscar Wilde Miscellaneous: A Florentine Tragedy - a Fragment, and La Sainte Courtisane - a Fragment

Oscar Wilde Miscellaneous: A Florentine Tragedy - a Fragment, and La Sainte Courtisane - a Fragment The Canterville Ghost (Illustrated by WALLACE GOLDSMITH)

The Canterville Ghost (Illustrated by WALLACE GOLDSMITH) Complete Works of Oscar Wilde

Complete Works of Oscar Wilde The Picture of Dorian Gray: The Uncensored Original Text (Annotated) (First Ebook Edition)

The Picture of Dorian Gray: The Uncensored Original Text (Annotated) (First Ebook Edition) Fifty Shades of Dorian Gray

Fifty Shades of Dorian Gray Oscar Wilde's Stories for All Ages

Oscar Wilde's Stories for All Ages The Happy Prince & Other Stories (Puffin Classics Relaunch)

The Happy Prince & Other Stories (Puffin Classics Relaunch)